The Alienation Effect in Brecht’s “The Good Person of Szechwan”

Brecht’s The Good Person of Szechwan is a play that opens with Wang, a water boy and his search for the Gods who are visiting Szechwan. The Gods are looking for a place to stay, and in spite of Wang’s assurances that they will be able to find a lodge, no one in Szechwan believes or is willing to host the Gods. Shen Tai, a prostitute, offers to have the Gods stay with her.

The Good Person of Szechwan was written by Brecht in 1943. The play opens with Wang, a water seller who is on a search for Gods who are visiting Szechwan. The Gods are on earth, searching for someone who is ‘good’ in order to restore their faith in humanity. They are looking for a place to stay, and in spite of Wang’s assurances that they will be able to find a lodge, no one in Szechwan believes or is willing to host the Gods. Shen Teh, a prostitute, offers to have the Gods stay with her. In return, the Gods thank her by giving her 1000 silver dollars. Through the setting, characters and narrative structure Brecht employs the use of verfremdungseffekt, translated as the ‘alienation effect’ (Krasner 170).

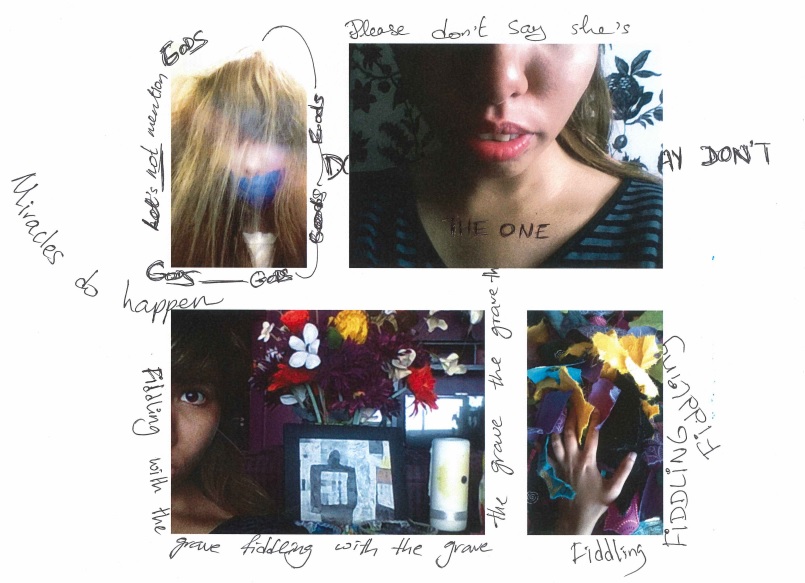

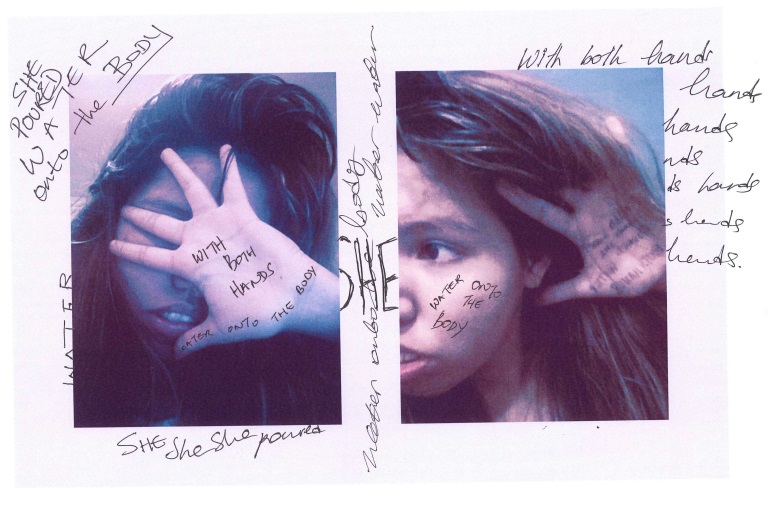

Brecht borrows from Russian formalist critic Victor Shklovsky’s concept of ‘Ostranenie’, which is center or making things strange dissimilar (Krasner 170). Ostranenie is centered on defamiliarize and making things seems strange. The alienation effect was not solely focused on a style of acting, but a style of performance itself. Brecht wanted to consider “delineat[ing] the separate components of acting, directing, and set design rather than unifying them” (Krasner 171). Additionally unlike dramatic theatre, Brecht did not aim to make an audience empathize with his characters. In fact, he wanted the audience to actively be aware of the fact that they are watching a play that is staged and not something that is real. Brecht emphasizes that “if empathy makes something ordinary of a special event, alienation [estrangement] makes something special of an ordinary one” (Krasner 170). When examining Shen Teh specifically, her occupation alienates her from the rest of the townspeople. On a fundamental level, she is a singular character, trying to do good. Though her intention to stay true to the morals she believes in does not shift over the course of the play, her interactions with other characters do. After buying a tobacconist shop, several people show up at her store asking her for favours, to which she complies to. The turning point in the character of Shen Teh however is when she adopts the persona of Shui Tai. Throughout the course of the play, Shen Teh and her cousin Shui Tai are seen as distinct characters. Shen Teh is compassionate and even vulnerable as she lets people take advantage of her. Shui Tai on the other hand, comes across as rather unemotional and not easily swayed by the troubles of others.

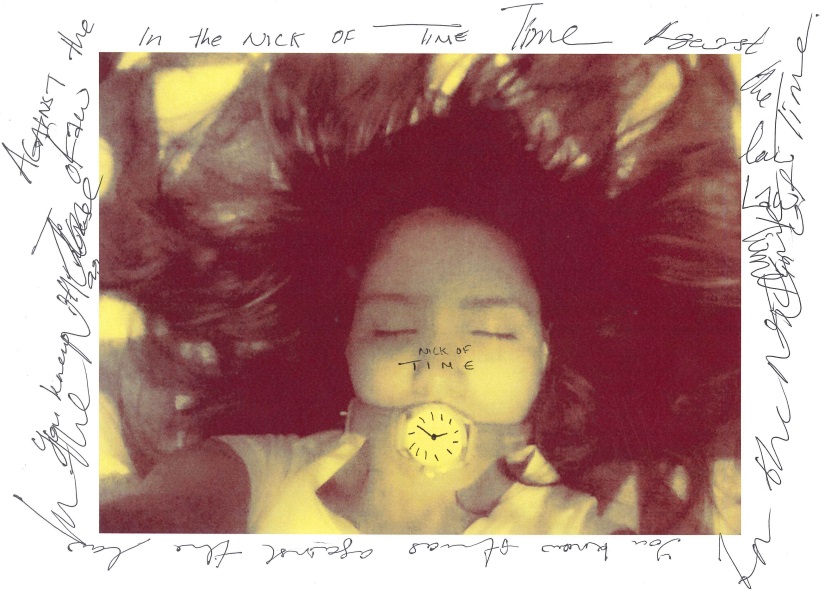

Aside from singular characters, Brecht’s alienation effect is closely tied with the narrative structure of the play. There is poetry and song intertwined in the narrative that add a degree of complexity and non-linearity to the play. In epic theater and Brecht’s work is “by design disjunctive, deliberately lurching from one scene to another. It is meant to replicate the circus” (Krasner 171). In between every scene or two, Brecht writes an interlude. These interludes are either solely focused on Shen Teh, or on a conversation between Wang and the Gods. The interludes serve as a needed break to re-contextualize the story from the eyes of Shen Teh or the opening character, Wang. The idea though, that these characters are returned to and their characterization is affected by their relationships. In Scene 10, the Gods are seen as acknowledging that Shen Tai is a good person and should stay in Szechwan. However she must deal with the people she made promises to and let down. Though she pleads with them to take her, the Gods simply leave her behind. Ultimately the Gods seem to have caused more problems that found a solution. If not for the reward they gave Shen Teh, she would not have been approached by people wanting to take advantage of her money and shop. In fact, the last stage direction before the epilogue reads that “As Shen Teh stretches desperately towards [the Gods] they disappear upwards, waving and smiling” (Brecht). There is such a sense of disconnect between Shen Teh and the Gods who have had an influence on her life. Shen The herself is alienated in the play. Her ‘goodness’ as a person becomes both an alienatioj reason that allows her interact with other characters in the story, but it is also the reason why the Gods stay and then leave.

The Gods:

Now let us go: the search at last is o’er

We have to hurry on!

Then give three cheers, and one cheer more

For the good person of Szechwan!